Examining the Orioles' recent draft strategy in a different light

The same kind of value-accumulation that is praised in the NFL draft isn't accepted in baseball. The Orioles have kind of been doing that recently. What has it been worth to their drafts?

Heston Kjerstad, the Orioles’ second overall pick in 2020, arrived this week at Aberdeen on his delayed ascent through the farm at a time when the way he entered the organization is back in the spotlight.

The Orioles hold the top pick in Sunday’s MLB draft, and there’s little certainty as to who they favor with that pivotal selection. There are myriad good candidates, but also the possibility like in 2020 with Kjerstad and 2021 with Colton Cowser that their view of the best player at their pick won’t align with the industry’s – and that signing bonuses might play a part in it.

Kjerstad is far enough removed from that to have some perspective on the discourse around his own pick, even as others may still be stuck on it.

“The guys that are getting paid to do the job are the ones that made the selection, and they believed in me,” he said Tuesday in Aberdeen. “If they believe in me, that’s all I need, is the team that selected me to give me the chance. … From there, it’s just proving to everyone else why I was selected there.”

That’s obviously been delayed for Kjerstad, whose affiliated debut came two years after he was drafted after he was diagnosed with myocarditis. What he’s shown so far – batting .463 with a 1.201 OPS in a month at Delmarva – show it would be foolish to give up on him.

But what if there was, from a strictly value-based way, to examine the Orioles’ decisions in the last few drafts without tying it to the outcome of an arduous player development process in a draft that produces far fewer hits than misses?

I was fascinated to see back around NFL draft time that Orioles assistant general manager Sig Mejdal spent a day in the Ravens’ draft room with his pal Eric Decosta, the general manager there. The two connected when DeCosta sought Mejdal’s advise in how to incorporate analytics into the draft process when Mejdal and Mike Elias were in Houston, and their hirings in Baltimore brought proximity to the relationship.

Perhaps because the NFL draft is the most high-profile and gives the most immediate returns, anyone who talks about the MLB draft takes great pains to explain how dissimilar they are to the common fan. It’s not entirely inaccurate. The MLB draft features high school and college players, is much longer, doesn’t involve drafting for current major league need, and features far less public knowledge about players than the NFL draft.

There are major differences, but two things seem similar. One is a team wants as many picks as possible, because there’s no science to it, and the more chances you have to get top talent a team has, the better chance some of those hit. The other is that, well, value is value.

It’s struck me over the last few years that the same kinds of moves that the Ravens make in accumulating mid-round draft picks and still selecting players they like early in the draft is much better-received than the Orioles’ underslot gambits that, essentially, accomplish the same thing.

MLB teams can’t trade draft picks, outside the handful of competitive balance picks assigned each year. But they can use their bonus pool to, effectively, give them more chances at accumulating the kind of talent having extra second- and third-round picks could bring. The more cracks at top talent a team has, presumably, the more chances they have to hit one them.

There are a lot of different methodologies used to quantify NFL draft pick value, but I have always liked Chase Stuart’s approximate value (AV) chart, which is a little less top-heavy than the traditional Jimmy Johnson chart that places a premium value on the very top picks each year. (The bias in using that system for this kind of exercise is not lost on me, though it’s not intentional.)

Where the Orioles are concerned, they have two very different drafts in which they’ve signed players for below top pick slot to examine. Kjerstad’s 2020 draft, which featured just five rounds and six picks for the Orioles, is one of them.

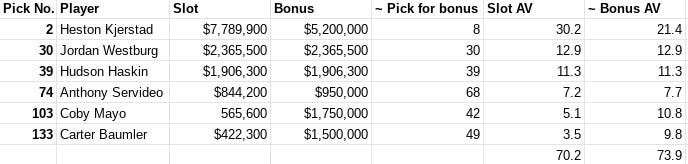

They entered that draft with picks 2, 30, 39, 74, 103, and 133. By signing Kjerstad for $5.2 million – a bonus approximately in line with the eighth pick that year – instead of the pick’s slot value of $7,789,900, they saved nearly $2.6 million to use on other picks. That went to prep third baseman Coby Mayo ($1.75 million bonus at a $565,600 slot for pick 103) and Carter Baumler ($1.5 million bonus at a $422,300 slot for pick 133), plus to a lesser extent Anthony Servideo ($950,000 against an $844,200 slot at pick 74).

To look at it from a pick-trading perspective, they essentially swapped No. 2 for No. 8, 42, 49, and 68. Where bonus capability is concerned, and bonuses are often commensurate with talent, they went from having a first-round pick, a sandwich pick, and picks in rounds two through five to a first-round pick, a sandwich pick, three seconds, and a third.

Using the draft value formula linked above, the AV added for the picks was 3.7, the equivalent of a fourth-round pick. However it’s sliced, there’s a lot of value added – though much of it rides on Kjerstad’s ability to be the impact player the Orioles still expect him to be, as well as the value added by the promising combination of Mayo and Baumler.

The 2021 draft, headlined by surging outfielder Colton Cowser, featured 20 rounds and thus a little more complication for something like this. The AV chart only goes to pick 224 – the NFL draft is much shorter than the MLB draft – so anything below that for these purposes has to be considered found value.

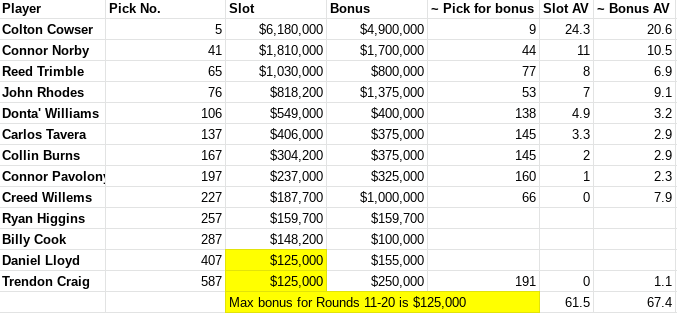

Cowser was the fifth overall pick with a bonus slot of $6.18 million, and signed for $4.9 million, commensurate with the No. 9 pick. After him came much bonus pool maneuvering, which is probably easier consumed as a chart.

The main overslot picks later in the draft were third-round pick John Rhodes, who signed for $1.375 million at pick No. 76 (slot: $818,200), and a $1 bonus to Creed Willems in the eighth round, well over the recommended slot of $187,700.

This one isn’t as tidy from a “trading picks” perspective, but in terms of the AV of the commensurate picks for the bonuses they paid out versus the AV of the picks they entered the day with, they added 5.9 points of value – commensurate with an extra mid-third round pick. Equating the bonuses they gave out to the picks associated gave them the slot value of five of the first 77 picks as opposed to four of the first 76, which they entered with.

Again, most of this rides on Cowser, plus the development of Rhodes and Willems, as determining whether the maneuvering was worth it.

There are plenty of examples of the Astros’ drafts when Elias ran scouting there being geared around maximizing the talent their bonus pool could bring in, but there are also examples like the Orioles’ 2019 draft where they went about that in a more traditional way. Adley Rutschman took a mild discount as the top overall pick, but the Orioles gave Gunnar Henderson an above-slot bonus of $2.3 million – the slot value of the 31st pick – when they took him at 42 overall.

They found some of the extra $520,000 through Rutschman’s savings, but also took several low-bonus players on the second day to pass on the savings there as well. I’m sure they can find a $20,000 senior sign or two at the end of the second day who is just as good as someone who would command a slot-level bonus.

That could easily be the path this year, made more so by the fact that their competitive balance Round A pick at 32 overall and the Marlins’ Round B pick (No. 67) acquired in spring training give them a massive bonus pool to work with, to the point that they don’t need to play a money game with their top pick this year.

Maybe they will anyway. As with the last two years, it would overshadow the players they actually take in some corners of the world. And as with those, there’s no way to know whether it’s worth it or not. Perhaps this year, though, the process and valuation behind the picks can be viewed in the same way they would if the Ravens were making them.